Harry Moffitt: Eleven Bats book excerpt

Anthony “Harry” Moffitt is a Military Speaker & former SAS Team Commander turned practicing psychologist specialising in human-performance. He is an entrepreneur, researcher and Founder and Managing Director of Stotan Group: a human-performance consulting and coaching company. He has completed nearly 30 years’ service in the Australian Defence Force, mostly with Australia’s elite Special Air Service (SAS) Regiment, where he amassed almost 1000 days of active service over 11 deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq and Timor Leste, and other discrete commitments globally.

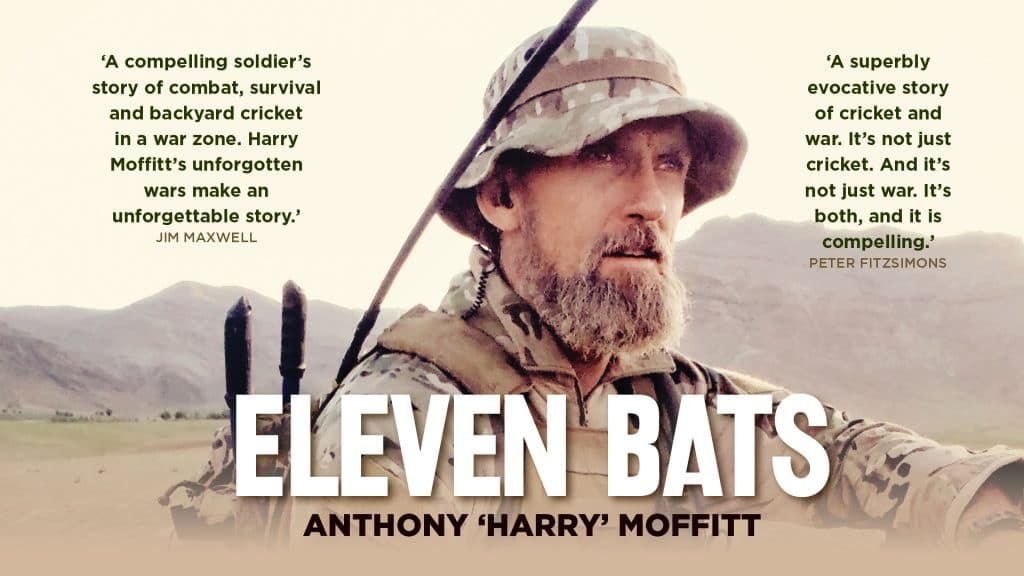

Harry has shared a chapter of his new book Eleven Bats.

ELEVEN BATS – Introduction

I never heard the explosion.

There must have been an almighty bang, because I was in the air feeling like I had been trampolined off a blanket held at the corners. Looking down between my legs, I saw the driver’s seat I had been sitting in and the steering wheel I had been holding. They were floating above the earth, along with the rest of the vehicle, which was now in two halves and, like me, airborne, out of control, useless and powerless. At the apex of my flight, time stood still. But I still can’t hear the explosion.

Everything else has the clarity of a slow-motion replay. It was Tuesday, 8 July 2008, early on a typically cloudless morning in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan. What I do know is that when I landed, my mate Sean McCarthy would be dead, and our interpreter Sammi would suffer injuries so severe he would lose his left leg. As I hung there in the perfect sky, I was still innocent of this knowledge. The only person I thought was going to die was me.

They say your life flashes before you. I have a crystal-clear memory, while I was floating in that eerie silence, of three images side by side, like a row of photographs on a mantelpiece. I had recently started a degree in psychology and I pictured my textbooks, which were in my backpack flying somewhere in the air with me.

I wondered if they would be damaged. The portrait in the centre of my imagination was of my wife, Danielle, and my kids, Georgia and Henry. I saw their faces looking up at me. There was no time to process any emotion. All I thought was, There they are, the most important people in my life. And to the other side, I saw the Applecross Cricket Club. We had won a grand final a few months earlier and the felt pennant was one of my most prized possessions.

Family, study, cricket. When you’re about to die, you learn what really matters to you.

—————–

My name is Sergeant Anthony Moffitt, though I am known as Harry. For nearly all my adult life I was a professional Australian soldier. I served more than twenty-five years in the Australian Army, including nearly twenty as an Operator and Team Leader in the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR, or SAS as it’s commonly called). I completed many operational tours and international engagements, amassing nearly one thousand days on active service in Afghanistan, Iraq and Timor-Leste. I spent roughly the same number of days again working with forces around the world.

Like many Australian soldiers in that period, I have been shot at, blown up, busted and broken, mentally drained, socially dislocated and spiritually, ethically and morally challenged. Unlike many Australian soldiers, I have been on hundreds, maybe thousands, of combat missions in that time. My family rode the rollercoaster, quietly determined to support me, which was not always easy for them given the tensions between warfare and modern social values.

Australia can be a testing place to pursue a profession of arms. In the past, we in the armed forces have been warned against wearing our uniform in public, which was frustrating, if understandable.

Many times over my career I have found myself defending ‘war’ and our defence forces against younger, progressive, educated people, and I don’t disagree with their attitudes or even the content of their arguments. I welcome having my thinking challenged, and my position on killing, combat and warfare has changed over the years. No one hates war and fighting more than me, especially as I have seen the results—the torn human flesh, the civilian impacts, and what it does to the minds of those in combat. But I have also seen what extreme ideologies can do, and sometimes we are called to help. I occasionally envy those who enjoy the comfort of seeing the world in black and white. But the world I have seen is not that simple.

During my service, I didn’t turn into the quintessential tough soldier: a strong, imposing, striking warrior, hardened in the heat of combat, dark and contemplative, with an air of control and decisiveness. I am skinny, anxious and easily distracted. My journey has been less about combat and courage and more about adventure and the determination to understand and overcome my weaknesses. I merely squeezed everything I could out of my limited resources.

During my years of service, I became known in the SAS for organising cricket games within the unit, in backyards, streets, military compounds and even ‘outside the wire’ wherever I travelled with combat teams. I was also a playing member, Aubrey King medal-winner (awarded for end-of-season trip shenanigans), and former vice-president of my beloved Applecross Cricket Club over

a twenty-year career (and I am still available for selection!). I enjoy travelling internationally to watch Test cricket, and at home I listen to it passionately on ABC or BBC radio. Like many Australians, I am avid about Test cricket in particular, which I consider has much in common with combat operations in its strategic and tactical design, planning and execution. Cricket, like war fighting, involves long periods of thinking and plotting, punctuated by moments of extreme tension and action. Often, nothing consequential comes out of these moments but sometimes they produce the highest drama.

This book is about my life inside and outside the army, and about how I changed as a person during my years as a soldier. It is also about how the game of cricket became a framework around which

I was able to better understand my experience and communicate with others. Cricket provided me and some of my fellow soldiers with a purpose when there seemed to be none. An escape when one was needed. A conversation when silence needed breaking. A moment of forgetting the long time we were spending away from family and friends. It even represented a therapy between deployments, when I built not only a career with Applecross but the Moffitt Backyard Cricket Ground, my very own MCG.

Cricket drew teams and individuals closer together, building ties between us and the people in Afghanistan, Iraq and Timor-Leste we were working to protect. It even forged links with some of those we considered our adversaries; in some ways, cricket transcended death itself.

The matches that broke out among us on airfields, in Q stores and on Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) were always a superb balance of competitiveness and ‘spirit of the game’. The banter came thick and fast, and was not always politically correct (‘You swing like your mother, Harry!’ or ‘. . . like a shithouse door in a thunderstorm!’). Allegiances would form along state lines, which is common in the military, whatever the sport. Organised games of rugby union and league, AFL, basketball and other sports are an enormous component of military culture. But cricket seemed to span all states. I loved how cricket was the broadest church, accessible to every man, woman and child. Break out a match and everyone gets a hit, a bowl, and a chance to catch a lofted shot to cow corner. Cricket can be played anywhere: inside a kitchen, on a two-metre wide strip behind the shitters, or inside an aircraft hangar.

Cricket has been played in many battle zones. Most notably in Australian military history, Shell Green in Gallipoli hosted cricket matches as a ruse to trick the Turks into thinking everything was normal while the withdrawal was being prepared. In the shadows of the Sphinx, soldiers of the Light Horse played cricket before embarking on the assault on Beersheba in 1917. In a famous image, Albert ‘Tibby’ Cotter, an Australian Test pace bowler, is shown slogging a ball into the Egyptian desert. Cotter was killed in the charge at Beersheba, where he was a stretcher-bearer. He left stardom as a sporting celebrity to join the AIF but, not wanting to fight, chose what was arguably a more dangerous role. He is one of a handful of Australian Test cricketers who served on active duty, and an inspiring figure in my life.

Along my journey, as the importance of cricket impressed itself on me, I decided to keep the objects that gave form to the spirit of the game: the bats we used in these war zones. Over eleven years,

the collection grew to eleven bats. It became my habit—more than a habit, a necessary part of my preparation for each trip—to carry a cricket bat to wherever we deployed. It was also my habit to ensure that SAS team members and support staff signed the bats at the end of those deployments.

Our military equipment manifests courage and combat; my odd collection of cricket equipment manifests the humanity of modern warfare, the insanity and tragedy, the fear, the anxiety and trauma, punctuated by occasions of joy and camaraderie and black humour. These bats provide a tangible anchor for what has been a sometimes surreal journey.

Prime ministers have also signed the bats, two governors-general 6 as well as military generals, genuine royals and the Victoria Cross recipients Mark Donaldson and Ben Roberts-Smith.

Perhaps my favourite signatures are from a Timor-Leste deployment in 2006, the names of Xanana Gusmão, Mari Alkatiri, José Ramos-Horta and Alfredo Reinado—particularly these last two. Ramos-Horta’s and Reinado’s signatures are on the same bat only centimetres apart, a remarkable fact, as less than two years after they signed the bat, Reinado came down from the hills outside

Dili, tried to assassinate Ramos-Horta in his home, and was killed during this attempt.

I try not to have favourites, but I value this bat more than most.

Until my retirement, I hadn’t thought anyone else might be interested in the stories behind my cricket bats. A civilian friend once said to me over a beer, ‘You’ve got an amazing collection of bats, they should be on display.’ Later, while moving house and pulling the bats out of an old box, I wondered if these unique military artefacts might have something to say about the history and commitment of the SAS and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) over the last two decades. From the streets of Mogadishu to the jungles of Timor, the coastal plains of Kuwait to the Hindu Kush of Afghanistan, the western deserts of Iraq to the African and Middle Eastern areas of operations, among many other places, Australian soldiers had certainly seen a lot in this period. And although the SAS only comprised a tiny fraction of the defence force, we had been called on to do a disproportionate amount of the fighting. Perhaps a time would come when these bats could tell my story, and the story of the mates and the regiment I love so much.

The Australian War Memorial expressed an interest in displaying the bats; however, I was not ready to ‘donate’ them yet, as I wanted the chance to show them off a little. They have been on display at

the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne and at the MCG Long Room, where I was invited to talk through a few of the stories that accompany each bat. Rather than the typical ‘war stories’, I preferred to talk about the humour, humanity and psychology of modern combat. I found telling my stories therapeutic. I also liked to emphasise the impact of service on our families, too often forgotten in modern war narratives.

All eleven of my bats have been ‘outside the wire’ on combat, humanitarian and diplomatic missions and I believe they are inextricably intertwined with the service of Australian soldiers across the ages. Yet cricket is neither life nor war. Sports analogies, while they can carry important meaning, cannot be allowed to trivialise the gravity of fighting in war. Sport is entertainment, combat far from it. Sport is comparatively non-consequential next to the immeasurable after-effects of fighting in war. Sport is fleeting, while combat thunders down the ages. Sport is constrained, combat unconstrained. Sport has rules and an umpire who influences events; combat, most of the time, has neither, and when rules are broken and an ‘umpire’ steps in, it is a process that often takes place many years after the event. However, that does not nullify the value of sport during times of war. While war is tragic and traumatic and tears people apart, sport is fun, peaceful and brings people together. (When George Orwell described sport as ‘war minus the shooting’, he was using a rhetorical flourish; sport may indeed be ‘bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence’, as Orwell described, but, even at its worst, it’s still a long way short of war.)

It was war, not sport, that sent me flying into the air that day in Afghanistan in 2008; it was war that revealed what was important to me, and war that asked me how the hell I had got myself into

this situation.